Evolution of Multicellularity

The Evolution of Multicellularity |

Also see: Endosymbiotic Theory | |

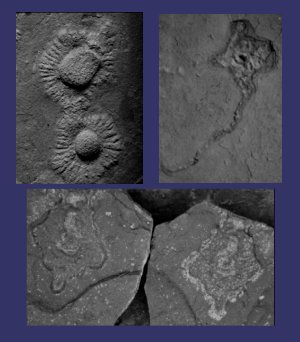

Putative Multicellular Macrofossils of the Francevillian Series of Gabon

While such fossils are always controversial, with some scientists insisting they are pseudofossils, the FB2 fossils do appear to be organisms that while spatially separated, also led a colonial existence. Most importantly, the cells may have been differentiated. Diffrentiated means they exhibit patterns of growth determined from the fossil morphologies that are suggestive of intercellular signaling and thus of mutually synchronized responses that are the hallmarks of multicellular organization. The evolutionary leap to multicellularity would require the distinct cells to adhere, communicate, and cooperate with one another, and to specialize their respective contributions to the aggregated organism. The aggregated organism would also need to reject cells providing to collective benefit (i.e., similar to immune rejection). This evolutionary leap to multicellularity is believed to have occurred repeatedly in the evolution of life, and through many different biological pathways. The distinct and independent cells evolved the means to symbiotically organize, thereby thrive, and with such organization ultimately becoming genetically regulated so the multicellular organism operates synergistically in energy production and consumption, survival, and reproduction. Presuming that the fossils of the Francevillian Series of Gabon are of ancient multicellular life, and possibly eukaryotes, it is interesting to consider that they were early in what is called the Boring Billion years of evolutionary stasis of such organisms, a stasis that would persist until the Ediacaran around 635 mya and the Cambrian Explosion at about 521 mya. References: El

Albani A, Bengtson S, Canfield DE, Bekker A, Macchiarelli R,

et al. (2010) Large colonial organisms with coordinated growth

in oxygenated environments 2.1 Gyr ago. Nature 466: 100–104. | ||

|

Fossil

Museum Navigation:

Home Geological Time Paleobiology Geological History Tree of Life Fossil Sites Fossils Evolution Fossil Record Museum Fossils | ||||||