Ammonites

Ammonite Fossils |

Also

see : |

|

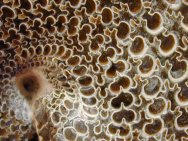

1**2 + 1**2 + . . . + F(n)**2 = F(n) x F(n+1) Or, is it the ammonite's shells, originally composed of aragonite, a carbonite mineral, which is unstable at standard temperature and pressure, and reverts to calcite over tens of millions of years. Actually, the shells inner surfaces had layers of nacre, or mother of pearl, an iridescent organic-inorganic composite (aragonite plates separated by proteins) secreted by the epithelial cells of some mollusk. During fossilization, the nacreous layer of some ammonites was chemically transformed into an iridescent material called ammolite, which is aragonite with varying mineral impurities that is considered to be an opal-like gemstone. Whether it is the shape or the shell, or both, ammonite fossils possess an inherent beauty seemingly pleasing to everyone’s eyes. Just as Fibonacci numbers are apparently ubiquitous in nature, so too are the ammonites, having left an extensive fossil record. From the time of their appearance, descending from nautiloids in the Upper Silurian to Lower Devonian, to their extinction with the dinosaurs, ammonites left their shell remains across the globe. Ammonites cyclically declined and radiated through the many extinction events that punctuated the Paleozoic and Mesozoic Eras and were extremely prolific in the Mesozoic. Ammonites are also a favorite subject of the artistically inclined individual that may cut, polish and mount them in various ways. The specimens below were chosen more for beauty and diversity than to tell a tale of ammonite evolution. | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Fossil

Museum Navigation:

Home Geological Time Paleobiology Geological History Tree of Life Fossil Sites Fossils Evolution Fossil Record Museum Fossils |

There

is just something intrinsic about ammonites (and nautiloids) that

is aesthetically pleasing to humans, and perhaps as well to our

less sentient cousins in Kingdom Animalia. Could it be Phi, the

Golden Number (= 1.61803….), ubiquitous in nature? Could

the pleasure be the ammonite's Fibonacci spiral, observed in galaxies,

the arrangement of leaves around a stem, and the shape of ammonite

and nautiloid shells?

There

is just something intrinsic about ammonites (and nautiloids) that

is aesthetically pleasing to humans, and perhaps as well to our

less sentient cousins in Kingdom Animalia. Could it be Phi, the

Golden Number (= 1.61803….), ubiquitous in nature? Could

the pleasure be the ammonite's Fibonacci spiral, observed in galaxies,

the arrangement of leaves around a stem, and the shape of ammonite

and nautiloid shells?