Russian Ordoviocian Trilobites

By the Ordovician

age (504 to 441 million years ago), the outcome of the solar energy- and floral

oxygen- driven

Cambrian explosion was manifest in the still accelerating diversity of trilobites

(fewer families than in the Cambrian, but more morphological variation). With

100 million years of selective pressure behind them, the trilobites from what

is today Russia developed unusual shapes, some with eyes on long stalks, others

with jagged spines. Ultimately these magnificent animals, in whole or part, met

their demise in earth's biggest ice age.

driven

Cambrian explosion was manifest in the still accelerating diversity of trilobites

(fewer families than in the Cambrian, but more morphological variation). With

100 million years of selective pressure behind them, the trilobites from what

is today Russia developed unusual shapes, some with eyes on long stalks, others

with jagged spines. Ultimately these magnificent animals, in whole or part, met

their demise in earth's biggest ice age.

During

the Ordovician, what is now Eastern Europe was a shallow inland sea. The fauna

was rich and diverse, and included the early vertebrates. This was the heart of

the age of the trilobite, a time when trilobites were not only diverse, but had

undergone adaptations yielding striking morphologies. The trilobites of Russia,

and specifically those coming from the Region near Saint Petersburg, are among

those most cherished by collectors. The reasons are several, their exotic forms,

superb preservation, and availablity.

During

the Ordovician, what is now Eastern Europe was a shallow inland sea. The fauna

was rich and diverse, and included the early vertebrates. This was the heart of

the age of the trilobite, a time when trilobites were not only diverse, but had

undergone adaptations yielding striking morphologies. The trilobites of Russia,

and specifically those coming from the Region near Saint Petersburg, are among

those most cherished by collectors. The reasons are several, their exotic forms,

superb preservation, and availablity.

The

Baltic limestone deposits that bear these trilobites was formed

in seas of about 70 - 330 feet in depth in what was probably

a large shallow basin. Scientists believe that this basin was

repeatedly blocked from contact with the sea to the west,resulting

in changes in both turbidity and salinity. Toward the end of

the early Ordovician the connection was re-established, with

substantial deterioration in visibilty in the seas due to the

influx of more turbid water. At this time some trilobites developed

raised eyes perhaps to impove their vision both of potential

prey as well as predators. The "periscope eyes" of

Asaphus Kowalewski were not yet

evident as this species evolved somewhat later. While many trilobites

were detritivores feeding on animal and plant debris in the

bottom muck, Asaphids are presumed to have been necrophagous,

meaning that they fed on dead carcasses, due to the shape of

the hypostoma (platform for mouthparts).

The

remains of this ancient Ordovician fauna is abundant in the baltic

The

remains of this ancient Ordovician fauna is abundant in the baltic  region, and

the city of Saint Pertersburg literally sets on a bed of Ordovician limestone.

Many Ordovician outcrops occur south of Saint Petersburg, and far and away the

most prolific yield of trilobites comes from the so-called Asery horizon that

is some 20 metters thick near the Wolchov River. Some 20 genera and 100 species

are found in exquisite, non-compressed preservation. Moreover, the limestone matrix

(in a manner similar to that of Devonian

Oklahoma) is relatively soft, enabling an expert with modern preparatory equipment

to produce finished fossils that can seem life-like. The trilobite exoskeletons

generally are extremely well preserved, and are a milk-chocolate color that contrasts

well against the lighter limestone. Horizons above and below show the progenitors

and descendents of trilobites from the Asery level, adding diversity to the trilobites

from the region, and adding to a wonderful story of decent with modification.

Some dozen trilobite families are represented, including Asaphidae, Illaenidae,

Cheiruridae, Encrinuridae, Raphiophoridea, Lichadidae, Remopleuridae, Harpedidea

and Phacopidae.

region, and

the city of Saint Pertersburg literally sets on a bed of Ordovician limestone.

Many Ordovician outcrops occur south of Saint Petersburg, and far and away the

most prolific yield of trilobites comes from the so-called Asery horizon that

is some 20 metters thick near the Wolchov River. Some 20 genera and 100 species

are found in exquisite, non-compressed preservation. Moreover, the limestone matrix

(in a manner similar to that of Devonian

Oklahoma) is relatively soft, enabling an expert with modern preparatory equipment

to produce finished fossils that can seem life-like. The trilobite exoskeletons

generally are extremely well preserved, and are a milk-chocolate color that contrasts

well against the lighter limestone. Horizons above and below show the progenitors

and descendents of trilobites from the Asery level, adding diversity to the trilobites

from the region, and adding to a wonderful story of decent with modification.

Some dozen trilobite families are represented, including Asaphidae, Illaenidae,

Cheiruridae, Encrinuridae, Raphiophoridea, Lichadidae, Remopleuridae, Harpedidea

and Phacopidae.

Asaphidae

Asaphidae

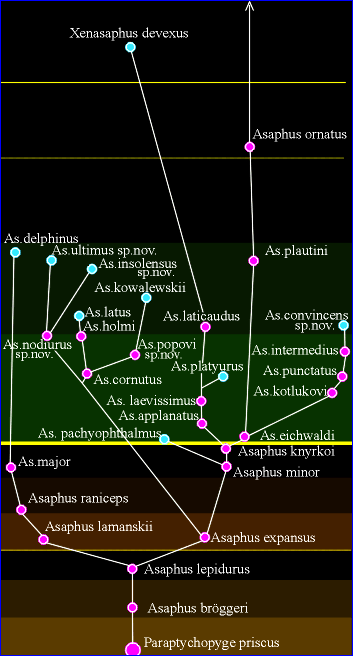

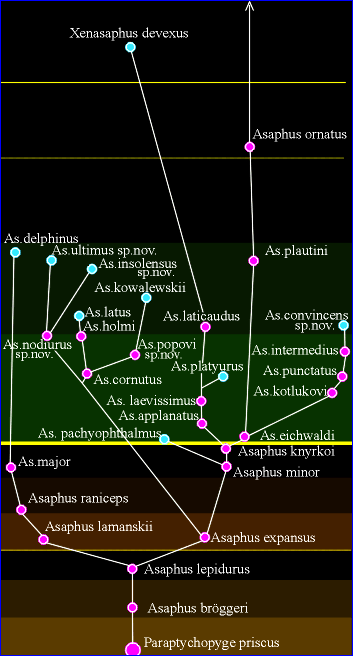

Far

and away the most prevalent, and the family best exhibiting

the outcome of adaptive strategies, is the family Asaphidae.

Some 30 species are believed

to

have descended from Asaphus broggeri that is found in the Wolchovian horizon,

with possibly Paraptychopyge as its sole ancestor. The figure shows the bushy

branching of Asaphidae as suggested by cladistic research spanning more than

a

century. Asaphus lepiderus replaced Asaphus broggeri, and represents a major

branching to: 1) the very similar Asaphus

expansus and 2) a new genus represented

by Asaphus

lamanskii. Asaphus lamanskii was successively superceded by Asaphus raniceps

and Asaphus major that occur in the kunda horizon, and the much later Middle

Ordovician

termination of the branch with Asaphus

delphinus; mysteriously, no intermediate

forms are known. Asaphus

expansus apparently gave

rise to the remainder of the Asaphus line, which itself would undergo additional

and exotic diversification. Asaphus applanatus began a tendency to larger

width

and genal angle, such as the impressive Asaphus

platyurus. Also impressive was the succession of Asaphus kotlukovi, Asaphus

punctatus, Asaphus intermedius and Asaphus convincens that express progressively

higher eye stalks. The same tendency of adaptation occured in a line that includes

Asaphus cornutus and Asaphus

kowalewskii, among

several others. The Asery layer captures some 2 million years of rapid adaptive

radiation, apparently in response to environmental challenges such as a more

shallow

sea, increased seaweed and higher acidity. The last descendents of Asaphus disappear

in the layers of the Upper Ordovician, manifest evidence that adaptation has

its

limits.

region, and

the city of Saint Pertersburg literally sets on a bed of Ordovician limestone.

Many Ordovician outcrops occur south of Saint Petersburg, and far and away the

most prolific yield of trilobites comes from the so-called Asery horizon that

is some 20 metters thick near the Wolchov River. Some 20 genera and 100 species

are found in exquisite, non-compressed preservation. Moreover, the limestone matrix

(in a manner similar to that of

region, and

the city of Saint Pertersburg literally sets on a bed of Ordovician limestone.

Many Ordovician outcrops occur south of Saint Petersburg, and far and away the

most prolific yield of trilobites comes from the so-called Asery horizon that

is some 20 metters thick near the Wolchov River. Some 20 genera and 100 species

are found in exquisite, non-compressed preservation. Moreover, the limestone matrix

(in a manner similar to that of