Chengjiang Maotianshan Shales

Chengjiang Maotianshan Shales FossilsEarly Cambrian: 525 million years ago |

Related

Interest: |

An Early Cambrian Lagerstatte and Window to the "Cambrian Explosion" |

| The

Chengjiang Maotianshan Shales is a Konservat lagerstatte in

the Yunning Province of China, also known as the Chengjiang

Biota

or the Maotianshan shales, is an extraordinary

fossil site providing the oldest Cambrian

occurrence of diverse and well-preserved soft-bodied metazoan

fossils. While the first unequivocal fossils of multicellular

organisms are from the Ediacaran faunas dating to about 565 million

years ago during the Vendian Period of the Proterozoic, these

are impression ichnofossils of soft-bodied organisms. In contrast,

the Chengjiang Biota

(about 525 to 520 million years ago), like the younger Burgess

Shale fossils in British Columbia, Canada (about 515 million

years ago), were formed by rare circumstances that enabled

preservation

of soft body parts. Chengjiang is one of some 40 known Cambrian

localities that exhibit Burgess Shale-like, exquisite preservation

of soft tissues. Among these, due to the remarkable fossil discoveries

beginning in the 1980s, Chengjiang lagerstatte stands alone

in

providing insights, many in dispute, for understanding of the

paleobiology of multicellular animals in general, and chordates

in particular. Many new discoveries can be anticipated, as well

as revisions to the evolutionary interpretations of past discoveries.

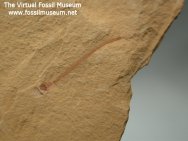

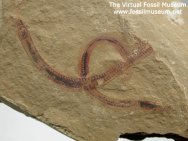

Maotianshan Shales fossils exhibit impressive animal diversity, many with their soft-tissue parts preserved. The faunal distribution spans across annelid worms, arthropods (including trilobites), primitive chordates, echinoderms, hemichordates, medusiforms, priapulids worms and sponges, and many more -- see an up to date list of Chengjiang Biota here. Of particular significance are the putative first agnathan fish (jawless fish). There are also numerous problematic animals, some of which may have left no descendents, and therefore constitute failed evolutionary attempts at diversity. As a whole, scientists have enormous work ahead interpreting the Chengjiang fossil record, and unraveling the many mysteries in this exquisite rock record of early Cambrian life. The

fossils are found in a 50 meter thick section of mudstone known

as the Maotianshan Shale, named for a Although fossils from the region have been known since the early 1900s, it was the discovery of the trilobita form Misszhouia (Naraoia) longicaudata on July 1, 1984 by Hou Xian-guang that led to the recognition of this exceptional soft-body lagerstatte. Unlike many fossil deposits, those of Chengjiang and the younger Burgess Shale show exceptional preservation of nonmineralized body parts and internal soft tissues, affording us far more information than could be gleaned from preservation of hard skeletal elements alone.

The Yu'anshan Member extends over tens of thousands of square kilometers of eastern Yunnan Province, and thus the Chengjiang biota is now known from various locations within the region. Nonetheless, the Chengjiang biota retains the name of the location at which it was first discovered. Some important locations are at Eriacun, Mafang, Haikou, and Kafuquing. It is at Eriacun that the world's oldest known vertebrates have been found.

The

sponges

(Phylum Porifera) are the second most diverse group after the

arthropods with the Desmospongea

(tubular sponges) the dominant type. Leptomitus. Leptomitella,

and Choialla are examples. The Hexactinellids (glass sponges)

are found as well, although they are far more rare. Haliochondrites

and Quadrolaminella are examples of this type. Many sponges have

been found buried where they lived, and so are often found articulated. The worms are represented by numerous specimens from the Chengjiang biota. The phylum Nematomorpha has been attributed to the genus Cricocosmia which has a long proboscis armed with spines. Some scientists ally it with the Priapulida (priapulid worms), and others with the paleoscolcid worms, indicative of the fact that the taxonomy of members of this fauna is still in a state of flux. Other examples are Maotianshania and Paleoscolex. The Priapulida are represented by Paleopriapulites, Acosmia, Sicyophorus, and others. The priapulids were a common component of the Cambrian marine faunas throughout the world.

The

Phylum Chordata

is that to which all vertebrates belong. Several examples are

found within the Chengjiang biota. As the earliest known vertebrate,

the most renowned is Myllokunmingia, which

Shu (2006) recently described an Ediacaran-vendiobont-like animal, Stromatoveris psygmoglena, gen. sp.nov., with features reminiscent of ctenophores which resemble jellyfish (radiate), but other characteristics suggestive of Bilaterans (Triploblasts with bilateral symmetry). Stromatoveris is a putative missing link between Ediacaran fronds and Cambrian ctenophores. The Chengjiang Biota is an incredible lagerstatte by all measures, including the enormous diversity and early appearance in the fossil record, and also the exquisite degree of detail of the preservation of its specimens. It affords us a unique opportunity to learn about these wonderful creatures so near the initial radiation of life to the forms of today known as the Cambrian Explosion. This amazing diversity was hailed throughout the world as one of the most important fossil finds of the 20th Century. Because of its unique value to science, the Chengjiang lagerstatte was placed on China's first list of A-class national geological parks in 2001. Chengjiang County has plans to apply for a World Natural Heritage designation for its deposits. Chengjiang is an underdeveloped county having rich phosphate deposits that are found both above and below the formation holding the lagerstatte. They have been exploited in part through efforts that began at about the same time that Hou Xian-guang discovered the deposits that bear these exceptional fossils, with phosphate mining bringing in some 2/3 of the county's revenue in 2003. Efforts are underway to close the region to mining to support the county's efforts to attain Heritage Status. A consequence of this has been renewed mining efforts in the region which threaten the fossil-bearing strata due to erosion, slumping of overburden, and simple destruction by the mining efforts. Chengjiang County faces the dilemma between calls for preservation of the treasure trove of early Cambrian fossils to which it is steward and the economic reliance it has on the phosphate industry. It is hoped that a balance between exploitation and restoration of the land can be achieved while there is still time. |

| Fossil

Museum Navigation:

Home Geological Time Paleobiology Geological History Tree of Life Fossil Sites Fossils Evolution Fossil Record Museum Fossils |